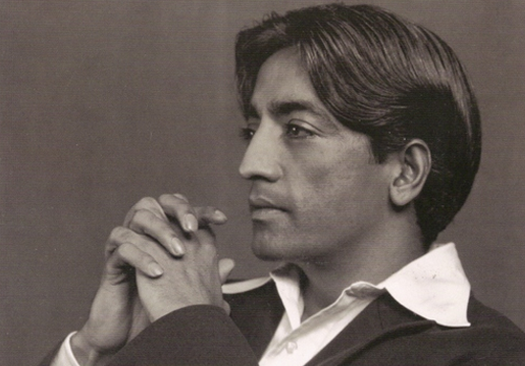

"If one wishes to know that

which is truth, one must be totally free from all religions, from all

conditioning, from all dogmas, from all beliefs, from all authority which makes

one conform, which means, essentially, standing completely alone, and that is very

arduous…" - Krishnamurti

“Each

philosopher, each bard, each actor, has only done for me, as by a delegate,

what one day I can do for myself.” - Ralph Waldo Emerson

The most important theme I

took away from Emerson’s essay “The American Scholar,” is the importance of discovering

truth for ourselves, by ourselves, not by simply imitating those who came

before us, but to stand on your own, as a light unto yourself. That we must use the past, not as a crutch,

but as inspiration and inspiration only.

For to imitate is regurgitate, and destroy all personal discovery and

inquiry. To come to a conclusion based

on the past puts an end to your own curiosity and experimentation. When one imitates, there is no searching, no

inquiry that one must undergo because it is all done for you. So, essentially this quote is about imitation

versus authenticity. Emerson rails against

a certain kind of intellectual, the “bookworm” as we discussed in class, or,

the person attached to literature as a kind of fetish. The bookworm imitates what is read, idealizes

it, but does not put it into practice.

The bookworm discovers nothing for themselves, they are stuck in the

past, and nothing is new for them. The “mind

of the past” is another important theme of “The American Scholar.” By this, Emerson is referring not only the

wealth of literature, philosophy, and culture of the past, but the modern mind

which is overshadowed and so crippled by these things. No matter what we do, the great figures of

the past, Shakespeare, Chaucer, among others, loom over the English writer, we

must always live up to the standards of genius.

In order to do this, according to Emerson, we imitate genius, we

emulate, we “Shakespearize,” but we ultimately have no genius for

ourselves. So the task of the true scholar

is then, through a return to nature, a return to reality, to become free of the

past and to seek to create for ourselves.

If the past has value, it is for inspiration, so that we may discover

our own genius now. This entire

sentiment brings to mind a more modern day spiritual teacher name Krishnamurti.

Krishnamurti once said, “We have all become good gramophone records.” In other words, we all imitate, but few of us

stand on our own. So when Emerson says, “what

one day I can do for myself, he is saying that in the end, you must discover

the truth for yourself, only then should you accept it.